How can creative writing enrich coaching and NLP?

As a budding author of fiction, my wife Anna arranged a creative writing lesson for me with her friend and author Hattie Edmonds. I was amazed to note how the ‘process’ fitted nearly exactly into Dilts’ & Gilligan’s six-step Generative Coaching structure. It also featured many principles I was familiar with from my job as an NLP trainer. I hope this blog will show how coaching can utilise the ancient wisdom of the narrative structure to promote significant change. I also hope that it will provide a broad template to write or follow any other creative endeavour.

Firstly, let me contrast the six steps of Generative Coaching with the writing process:

1. Open a COACH field

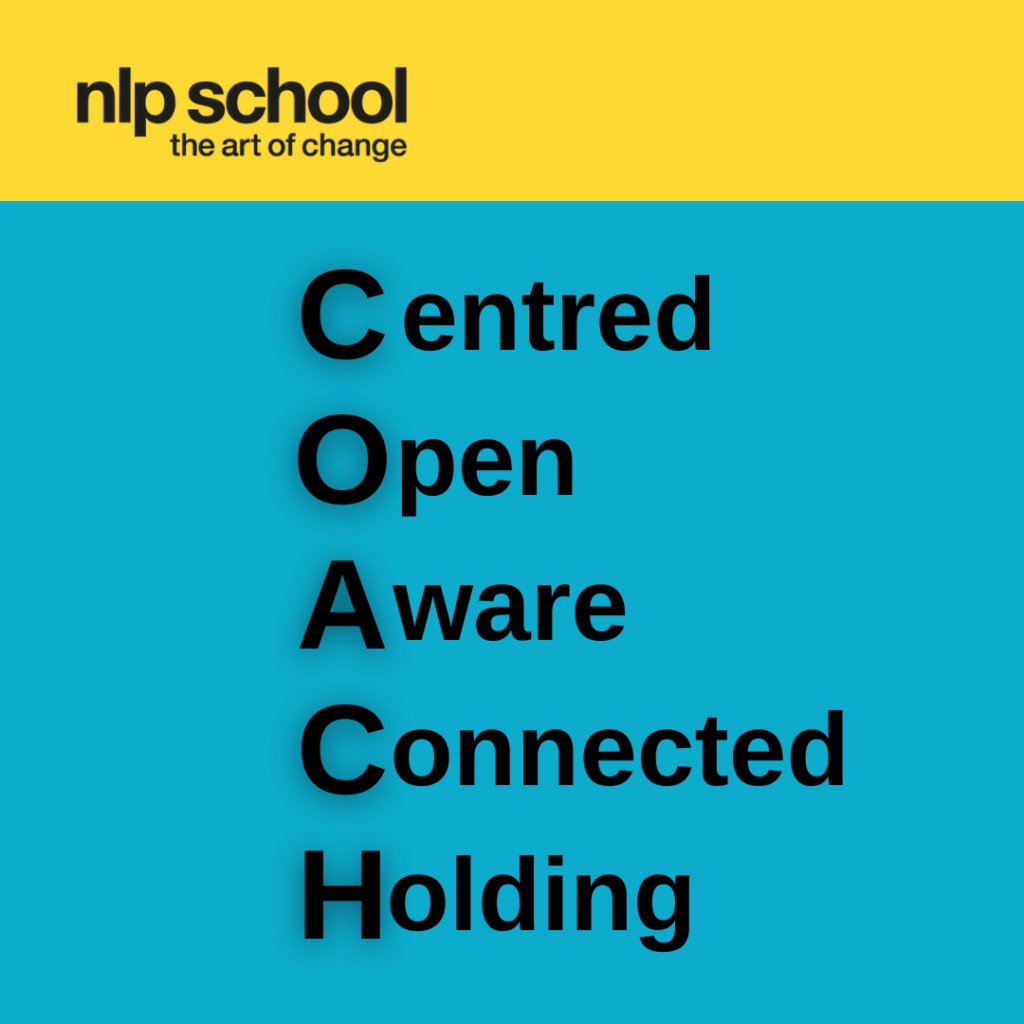

This means start a session with some form of ritual to help your client clear their mind. COACH is an acronym created by Robert Dilts to follow a meditative process which I can summarise as:

Centring yourself; being Open to your feelings; being Aware of your thoughts; Connecting these three together so you can Hold whatever comes up.

A writer is also advised to take a few moments to start their workday with a brief meditation to access their innate creativity. Artists and performers commonly say they do their best work when they are relaxed, and it sort of ‘appears’ without much effort other than an intention to focus. The idea that creativity comes from some sort of wilful thinking process is, I believe, actually false and counterproductive; the first job of any artist is similar to meditation – to move your attention out of the thinking mind, yet to retain a balance between focused alertness and body relaxation.

COACH state, Dilts and Gilligan

2. Set intention / Goal

This step features an important distinction from traditional coaching – the client starts with an approximate idea of what they want to achieve; the coach is to then help them clarify and potentially shift from this initial starting point throughout the session. This step is described not just in as few words as possible, but the client is also encouraged to express the intention both visually and somatically (somehow with their body).

I have often found that asking a client to simply ‘notice where they feel it in their body,’ unleashes far more potent words and pictures. The saying, “show don’t tell” is also a classic bit of writing advice to allow the reader to work out the meaning via the behaviour of the characters. ‘Show’ means asking the client to literally ‘show’ the coach what success looks like with both a physical representation and metaphoric one. This symbolism also enables clients to strengthen their unconscious motivation towards achieving the goal.

The writer also needs to set some intention about what they want to achieve. There is often an argument about a story being either character driven, or plot driven – does the writer have a clear template of the plot which the characters then deliver, or do they let the interactions between the characters rewrite the original plot? The truth is probably a combination of both. The writer Ann Tyler said that her most creative (and enjoyable) moments are when the characters ‘come alive’ and she simply ‘sits back’ and allows the characters to do the writing. I have heard different versions of this described by all the writers I have researched.

Often a book consists of a series of subplots that sequentially develop the overriding narrative, like scenes in a movie. When a writer sits down to write they need to set an intention of what they want to do for the subplot they are writing that day; however, like a Generative Coach, allowing a looser intention rather than a fixed goal, provides for the characters to make unexpected and creative changes, thereby encouraging the characters to ‘come alive’.

3. Develop a Generative State

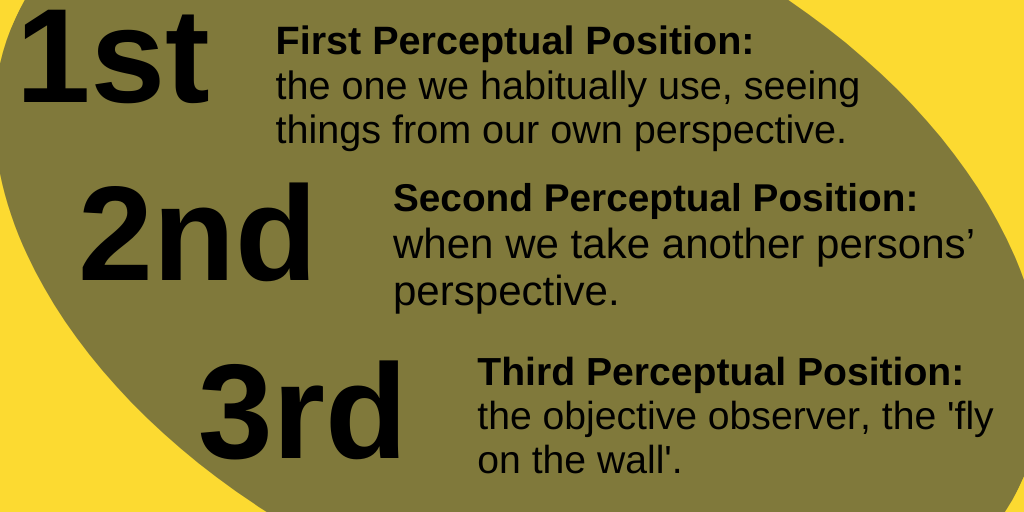

The 3rd step for the coach is to help the client access resources (either internal or external) to help move them into a truly creative state. Often the starting COACH state is also a ‘blank slate’ which is then adversely affected by thinking about the actual goal – this 3rd step allows the client to re-centre themselves so they can work out what else they need to move forward. A great source of resources comes from NLP perceptual positions – being able to borrow qualities from other people (2nd position) and to take a more detached and wider perspective (3rd position); of course, keeping what the client actually wants (1st position) firmly in mind.

For the writer the resources are very personal and often involve where they write, the research they do and the people they know – there is chameleon element of what resources do they need to take on the perspective of their characters. The writer Sebastian Faulks said that he had to fly to New York from London to bring one of his characters alive – the resources (historic bars and diners in Brooklyn) enabled him to inhabit the character and provided the needed inspiration.

From an NLP perceptive, the writer needs to pretend to embody that character i.e. take a 2nd position; there are also elements of the writer’s personality in every character so they can take a 1st position and finally gain a wider perspective, noticing the characters interact from a neutral observer or 3rd position. There are likely to be numerous switches between these perspectives to help the author develop the story. Interestingly, most books are written predominately from one of these perspectives, i.e. authors usually refer to the main character as I, he or she.

4. Take Action

Putting together a robust plan is the more managerial aspect of coaching. Part of the resources in the previous step is also the ability of the client to inhabit different parts of their own character. This can be neatly summarised by Robert Dilts’ Imagineering process, The Dreamer, the Realist and the Critic, these are based on three profoundly different attitudes spotted in Walt Disney’s character by an animator Robert interviewed.

The Dreamer allows for uninterrupted creativity, the Realist uses storyboarding, building a coherent plan, and lastly the Critic challenges the plan so it can be amended and improved.

The writer now needs to conceive the subplot in more detail, consider how the characters would react and interact and determine how it fits into the longer narrative arc of the story. Using the Disney process is an ideal way to refine this process.

5. Transforming Obstacles

Perhaps the most powerful step in Generative Coaching – the assumption that our ‘core wound’ is also the source of our greatest creativity and power. This principle is sometime phrased as ‘the problem is the solution’ which is a radical approach to change work. The idea is influenced by Stephen Gilligan’s Self-Relations approach and can also be found in Delozier & Grinders NLP Six-Step reframing process.

Writing is also therapeutic and arguably that is its prime job – to heal the author. As writer Stephen King put it, “Life isn’t a support system for art; it is the other way around.” This then provides a potential framework for all writing – the main character shares the same core wound as the author and the story structure is about overcoming the writer’s deepest fear.

This principle is well represented by the Hero’s Journey, a change process created by Robert Dilts based on the work of Joseph Campbell. Plot structure has been with us for well over 5000 years, with the first written fiction (the Samarian story of Gilgamesh) following this same structure.

It is reasonable to assume that humans would have shared similar stories by word-of-mouth for millennia before and we are ‘hardwired’ as a species to understand the world through story.

The structure is that the hero needs to face their own personal nemesis or demon to gain the elixir (the goal they seek). The demon represents their deepest fear and the elixir the thing they most want in life that this fear has prevented them from obtaining. Typically, the hero fails three times before defeating the demon, who then pops up a final 4th time known as the final ‘rug pulling’ – at this point the unsuspecting hero endures a final surprise attack by the demon and summons up the courage to conclusively defeat it.

6. Practices for Deepening the Changes

Stephen Gilligan points out that so often clients have an epiphany during a session that is not followed through afterwards. He therefore insists that if clients want to work with him, they must commit to working out some form of regular ongoing action between sessions to deliver on the changes they have discovered.

My own approach is to additionally offer optional accountability; where the client can choose to use me to check on their progress, but they remain responsible to manage their own commitments otherwise.

This step is also the ‘difference that makes the difference’ for successful writers – they must commit to write, regularly and consistently. Of all the writers I have studied, without exception they write everyday – certainly five days a week. The famous detective writer Ed McBain used an office and went there every weekday like a salaried employee, nine to five with an hour break for lunch. A more recent writer, and in my view the best currently in this genre, John Connolly talked of working daily and accepting that some days will be easier than others, but even on days that were hard, he would still sit at his desk and make the effort to write. To quote Thomas Edison, “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.”

Conclusion

I hope I have demonstrated that creative writing and creative nlp coaching are truly complementary. Great coaching understands that life is complex, and a client’s struggles more closely mirrors a narrative journey than a coaching process. It may take a client years to feel sufficiently motivated to profoundly change and to finally face their deepest fears. Indeed, it is often an unpredictable event that finally ‘pulls the rug’ and brings about that long awaited change. The key rule of coaching is that it is the client’s agenda – that also means that it is the client’s timeframe.

Although we can clearly see what someone else needs to do to improve their life, they still need to own and act upon that discovery themselves – ‘show don’t tell’ is a great motto for coaches and writers alike.

Did you like this post?

Then check out our events and courses

Sign up to our on demand e-learning!

Where to find us

For posts, events, free open days and more, follow NLP School on:

Where to find Robbie

Twitter: @RSteinhouse

LinkedIn: Robbie Steinhouse